|

The year 2021 is the 50th Anniversary of the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal National Historical Park becoming part of the National Park System. This park preserves the historic 19th Century transportation canal from Washington D.C. to Cumberland, Maryland. Since 2019, it has been ranked as the 11th most visited United States National Park, with Great Falls being the most visited location along the canal's 184.5 mile-long towpath. Many visitors stop at the Great Falls Tavern but never explore more than the canal's first 14.5 miles.

No road follows along beside the C&O Canal. For that reason, the towpath is most popular with hikers and bikers. However, I decided to stay out of the city and explore some of the lesser-visited C&O Canal highlights. Wanting to see as much as possible and knowing that I didn't have time to see it all, I decided to drive to different locations along the canal, doing a series of short hikes along the way.

There is so much history along the C&O Canal that I could almost feel the ghosts of the past walking along the towpath with me. I visited the canal in 2020 when all the visitor centers were closed, and I left with so many unanswered questions that I wished I had been better versed in the canal's history before I went. The C&O Canal stuck with me, giving me a need to understand the people, the mechanics of how locks worked, and many other things that this blog post took on a life of its own. Yes, I've been told in the past that I write too much. LOL

I hope I get a chance to complete this park one day. While I love historical sites, I found the C&O Canal even more interesting than I expected it to be. The history of the C&O Canal comes first, but if you aren't into that, scroll down to the section on the C&O Canal by towpath mile it is clearly marked below. The History of the C&O Canal

As America grew and expanded, the infrastructure was needed to send resources and supplies Westward. Dubbed "The Great National Project", the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal took 22 years to construct employing thousands of immigrants along the way.

As far back as 1785, George Washington had the idea for a canal. He advocated using waterways to connect the Eastern Seaboard to the Great Lakes and Ohio River. Washington formed the Patowmack Company to improve navigation on the Potomac River by bypassing its waterfalls and rapids. The C&O Canal incorporated these canals into their canal system. The transportation race was on when both the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal Company (C&O) and the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O) began construction on the same day, July 4, 1828. While it was initially not considered a race, B&O was soon competing with the C&O for property rights over the narrow right of way along the Potomac River. The construction routes of the two companies finally collided at Point of Rocks. A bitter and expensive four-year battle ensued, halting construction for both until 1832 when the courts ruled in the canal's favor. Even though C&O won the right of way, B&O won the race with their first train arriving in Cumberland on November 1, 1842. It was eight more years before the C&O Canal would make it to Cumberland on October 10, 1850. After spending 14 million dollars on its construction and failing to reach their intended goal of the Ohio River, C&O decided to stop the canal at Cumberland since they could not compete with rail’s speed or capacity, making it nearly obsolete.

Still yet, the 184.5-mile long C&O Canal was an important commercial link between the East and the West for almost a century. The business grew slowly; the canal was a major target of the Confederacy during the Civil War, and seasonal flooding was always an issue. It was only profitable for four years. During its peak, in the 1870s, the canal boats were moving almost a million tons of freight a year.

A devastating flood destroyed the canal in 1889, forcing the C&O Canal Company into bankruptcy. No boats moved for 18 months. Finally, to avoid letting the right of way fall into the hands of their rival company, Western Maryland Railroad, B&O as the primary creditor to the C&O Canal Company, took over the receivership under the name Consolidation Coal Company. This agreement made B&O responsible for maintenance and operations until 1938. As the canal's business began to dwindle, B&O started to sell off parts of the basin. Western Maryland Railway was able to purchased the canal's terminus, filling it in, and building a railroad station over it. By the early 1920s, the slow-moving canal boats could no longer compete with the railroad. The canal finally closed in 1924, after a flood destroyed much of its banks and locks. In 1938, when the receivership ended, B&O sold the canal to the United States Government for $2 million, which they paid to the primary holders of the 1844 and 1878 bond mortgages. Canallers - Life of the Canal Builders

The 184.5-miles of canal prism, originally 6 feet deep and 60 to 80 feet wide, was hand dug by the lowest-paid workers. It was back-breaking labor since they only had shovels, picks, and wheelbarrows at the time. Their days were spent in ditches, up to their waist in mud and water. It was dangerous and challenging work; injuries were common, maiming and even death occurred frequently.

Living conditions along the canal were very primitive. Many married laborers traveled with their families, living in makeshift shanty towns near their worksites. Wives were not employees of the C&O Company but managed the domestic life of the camp. Single laborers often slept in bunkhouses with 15 to 20 other men. These poor living conditions made serious illnesses a threat, and hunger was common. Epidemics commonly sweep down the canal line leaving a trail of bodies in its wake. Miserable living and work conditions made for fighting among the Canallers. C&O struggling financially, sometimes withheld wages. Work crews were often pitted against each other for jobs leading to sporadic unrest, violence, ethnic conflicts, riots, and strikes. The Lock Tender

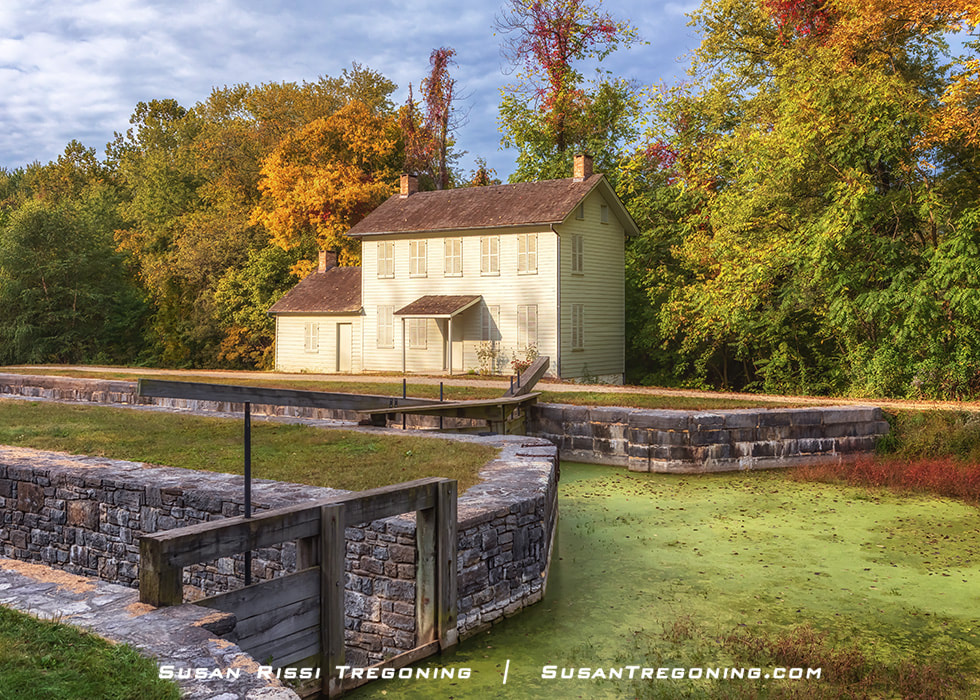

As soon as the construction of the canal was underway, the C&O company started looking for lock keepers. They wanted sober, reliable family men for these jobs. Every lock keeper received a lockhouse rent-free just a few feet from their lock, one acre of land for gardening and raising animals, and $150 a year (by 1870, it was $600). If he worked more than one lock, he was paid an additional $50 for each lock he tended (this increase to $150 by 1870). Besides lock tending, keepers were required to do minor repairs on the locks, maintain the canal water level and provide for any additional help they needed. For this reason, married men with large families were the perfect candidates for the job.

Lock tending was hard work. A lock keeper was expected to work 24 hours a day/7 days a week/ 365 days a year. There was no time off since a canal boat could come through at any time of the day or night. The pay wasn’t much. It was about what an unskilled factory worker made in the city. The garden helped put food on the table, and any extra produce was traded for coal and other necessities. Many wives baked pies and bread to trade. Children helped with the locks, and in the garden, they were also expected to fish and hunt for meat. C&O paid a bounty reward for muskrat, which was another way the kids helped bring in extra money. C&O also allowed tenders to rent rooms to travelers if they had the space.

The canal was a 184.5-mile long lineal community with as many as 530 canal boats on the water at any given time. The locks were common stopping points, so they became small communities and gathering places with grocery stores, and feed stores opening up nearby.

C&O made it attractive for merchants to set up shop along the canal and the merchants were the only ones to get wealthy off the canal venture. The annual rent for a feed store was $36 a year. In the 1870s, the mules used for towing the canal boats were consuming 25,000 barrels of corn, 3,840 bushels of oats, and thousands of tons of hay every year! Operating the Locks

When a canal boat passed through a lock, the boat captain put his life and livelihood into the hands of the lock tender. The wooden lock gates were a delicate balance between safety and efficiency. While the gates had to be lightweight enough that one man could operate them, they also had to be strong enough to hold back 140,000 gallons of water. A lock tender's job was to keep the water flow both in and out of the lock adjusted, minimizing risk to both the boat and lock.

Here is an example of the ten to fifteen-minute "lock through" process, while one person can do it, it's much easier with two.

The mules are unhitched and led downstream. Using ropes attached to the boat, the lock keeper guides the canal boat into the lock to prevent damage to the boat or the lock walls. Once the boat is inside the lock, it is tied off to snubbing posts to keep it secure. The lock tender pushes the large balance beams on either side of the lock to close the gate doors. The boat is now completely enclosed within the lock. Using a lock key, the lock keeper opens the butterfly or wicket valves at the gates' bottom to lower or raise the water level depending on which direction the canal boat is traveling. Once the water level is equalized in the direction the boat is headed, the lock gates are opened back up, and the boat is pulled out. The mules are hitched back up, and the boat continues on its way. Canawlers - The Canal Boatmen

The canal boat season was about eight months long, from March through December. Once the canal froze, they would drain all the water and the boats would sit on the bottom of the canal until Spring.

A trip down the canal took on average 5-7 days. Most canal boats could make two round trips per month. It took a crew of three to five to operate a canal boat, and the Captain paid them out of his earnings. Since the pay was already low, canal boats were usually family businesses. There were many women and children on the boats, and every member had their jobs. The Captain was generally on the bow (front) to grab a line or pole if something went wrong. "Women's work," cooking, cleaning, sewing, and taking care of the children was done by the tiller near the living quarters at the boat's stern (rear) since women were in charge of the steering too. Women were also responsible for changing the mule teams. Very young children were tethered to the deck, so they didn't fall off. By the time the kids reached seven years of age, they were extra hands on deck and responsible for the mules. They brushed, harnessed, fed them, cleaned the stable, and were the mule drivers walking with them along the towpath. At night, the children carried lanterns while riding the mules to help their parent's steer in the dark. It was such a transient lifestyle that the children that lived on the boats could not go to school during the canal season. Some children went to school during the off-season, but they were always so behind that most never learned much. Many were illiterate, as were their parents. It was common for the boys to grow up to captain boats and the girls to marry into canal boat families.

Directions when on the canal were upstream, downstream, riverside, and berm side. Most of the time, the towpath was on the riverside, but there are a few exceptions to that rule.

Downstream is traveling Cumberland to Washington DC. When traveling downstream, the boats primarily transported coal, but fresh produce, lumber, wheat, flour, oats, pork, grain, whisky, cement, and red sandstone were moved this way too. Upstream is traveling Washington DC to Cumberland. The boats traveling upstream transported goods and merchandise to the settlements and lock houses -- food such as salt, salted fish, oysters, potatoes, bricks, and manufactured goods. Canal boat operators were considered the "working poor." A boat captain doing two round-trips a month might clear about $50 a month; that’s equal to around $800 a month today. C&O made their money through tolls and traffic regulations. They charged a $15.50 toll each way to use the canal. The canal had a speed limit of 4 mph and if caught speeding the penalty was $5. The Mules

Mules were the preferred engines for the canal boats. Harnessed slantwise, which is one mule behind the other, they pulled the boat straighter than when harnessed abreast. Mules had to be re-shod about every other trip to Cumberland and sometime more often because of the extreme weight they were pulling.

During the canal's peak years of the 1870s, approximately 3000 mules were working on the C&O Canal. Most canal boat captains treated their mules like pets and cared for them like part of the family. They were well-fed, eating a diet of corn, hay, and oats. A boat captain typically owned four mules. Two worked while the other two rested in a Mule Stable on the bow of the boat. A workday for a pair of mules, known as a trick, was a six-hour shift covering about 16 miles while pulling a 90 x 14-foot barge carrying something like 120 tons of coal (an average load) along the canal.

During the winter off-season, most captains preferred to send their mules to a Mule Barn, paying a mule tender to care for them. Mules were not always well cared for at the barns and commonly underfed.

Boat captains preferred mules over horses because they had a horse's size and temperament and a donkey's strength and endurance. They were less prone to illness and injury, had longer life spans and work lives, and were cheaper to purchase. More sure-footed than horses, mules were less likely to trip and injure themselves when pulling such weighty loads. C&O Canal by Towpath Mile Marker

Once you get out past the D.C. Metro/Great Falls area, many of these locations are fairly rural. I have added addresses to sites when possible and GPS coordinates for the most rural locations. I did not always have cellular internet. Do not just rely on your cell phone for maps, have a GPS with you.

I traveled the C&O Canal in reverse, starting in Cumberland, Maryland, at the terminus. I reversed the information for this post since it makes more sense to count up the towpath miles. I could not resist visiting Great Falls Tavern since Great Falls is the #1 MUST SEE location but I didn't go any further into the city. I have added some brief notes for the C&O Canal sites that I missed. Many locations were skipped because of time constraints, and heavy rain showers hindered my last day on the Canal. If there wasn't a parking lot on-site or if it was raining at the time, I skipped it. I was very disappointed to miss out on towpath miles 16.7 - 22.8. I had planned to hit Great Falls again on my final day and then backtrack over some of the areas I missed, but I had to scrap the last day entirely because of the weather. There are some good-sized gaps between locations from towpath mile 14.5 through 88.1 for that reason. Overall, I was fortunate; the towpath was very dry while I was hiking it. I have read many accounts of the dirt trail being nothing but mud. Take that into consideration when planning your visit. 14.4 Great Falls Tavern

C&O Canal Visitors Center - 11710 Macarthur Blvd, Potomac, Maryland

This is the only location along the canal's length that collects National Park admission fees. The canal at the Great Falls Tavern is normally watered, but in 2020, I was disappointing to discover it was not.

The very first lock tender at Great Falls knowing that he had a special location because of the falls, convinced C&O to build an inn and allow him to run it.

The inn became a destination for people that lived in Washington DC. They could hop a packet boat in Georgetown, 14 miles away, and be there in 6 to 8 hours. It was the perfect weekend getaway! So popular that in the early 1900s, the Washington Railway and Electric Company ran a trolley line between Washington DC and Great Falls to make it more convenient.

The Great Falls Tavern is still the most popular canal location along the entire Chesapeake and Ohio Canal. In season, they do mule-drawn canal boat rides here. Besides the falls, don't miss seeing the Washington Aqueduct.

16.7 - Lock & Lockhouse 21 - Swains Lock - 10700 Swains Lock Road, Potomac, MD 39.031634, -77.243531

Part of the Canal Quarters program along with Lockhouses 6, 10, 22, 25, 28 and 49. 19.6 - Lock & Lockhouse 22 - Pennyfield - 39.0548142,-77.2948962 The lock that President Grover Cleveland visited often to fish. Canal Quarters info for Lockhouse 22. 22.1 - Lock 23 - Violettes Lock & Dam No. 2 ruins - 39.0670517, -77.328637 Double lock of Seneca red sandstone. 22.8 - Seneca Creek Aqueduct - 13025 Rileys Lock Rd, Poolesville, MD Rileys Lock 24 & Rileys Lockhouse - open on Saturdays in season. Seneca Stone Cutting Mill Ruins - Milled stone for Smithsonian Castle 30.9 - Edwards Ferry - Lock & Lockhouse 25

Lockhouse 25, is located in what was once the sleepy little town of Edwards Ferry, Maryland. Other than the lock and lockhouse, not much remains but the ruins of Jarboe's store. There is a nice boat ramp here, where the ferry boat use to land.

When the canal opened in 1833, the community of Edwards Ferry pretty much sprung up overnight. Edwards Ferry was the canal entry point for agricultural goods coming across the Potomac River from Virginia and headed to Georgetown.

During the Civil War, the north bank of the Potomac became a militarized border. Edward's Ferry was a strategic hot spot with both the Union and the Confederate troops using the ferry crossing. With the canal's proximity to the Potomac, it was often the Confederate force's target in an attempt to interrupt commerce. It was so bad that families living in the area were afraid to leave their homes, and the Union often occupied their fields while protecting the canal. As the war began to move south into Virginia, life in Edwards Ferry eventually calmed down.

Canal Quarters info for Lockhouse 25. End of Edwards Ferry Road, Poolesville, Maryland 39.1037595,-77.4726735

39.4 - Lock 26 - Woods Lock - filled in

41.5 - Lock 27 & Stone Lockhouse - Spinks Ferry Hike from Monocacy Aqueduct 42.2 - Monocacy Aqueduct

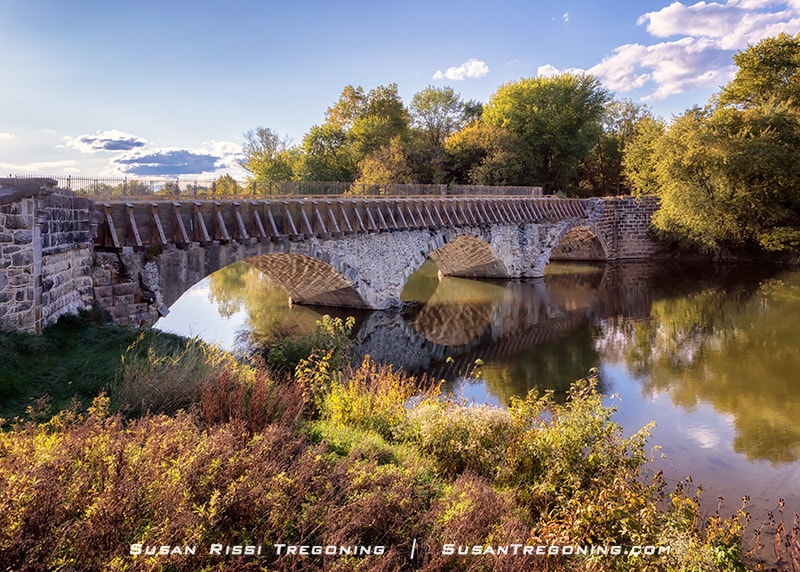

The Monocacy Aqueduct, also known as C&O Canal Aqueduct #2, is the largest of the 11 aqueducts constructed on the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal. Located near Dickerson, Maryland, it comprises seven arches, each spanning 54 feet. The aqueduct’s length is 438 feet from abutment to abutment. It crosses the Monocacy River just before it empties into the Potomac River.

Described as one of the finest aqueducts in the United States, its scale is considered a major engineering accomplishment for the time it was built, 1829-1833. Constructed mainly out of large quartzite stone blocks quarried from the base of Maryland's Sugarloaf Mountain, the stones were carefully placed together and painstakingly hand-shaped by masons once on site. The aqueduct cost $127,900 to construct. In 1972 after the Hurricane Agnes flood, engineers designed a steel banding system to stabilize the structure and installed steel rods to reinforce it. In 2004-2005, after restoring the Monocacy Aqueduct to its original state, they were able to remove the steel banding. 21115 Mouth of Monocacy Rd, Dickerson, Maryland 48.2 - Point of Rocks

magnificent Gothic Revival train station is situated on a small triangular plot at the spot where two sets of railroad tracks converge. The building is no longer open to the public, but is used by CSX for storage and offices.

Point of Rocks Train Station - 4000 Clay Street, Point of Rocks, Maryland This section of the towpath was closed when I visited. The C&O Canal towpath can be accessed from the parking lot near Point of Rocks boat ramp. 39.2730567, -77.5414085

49.0 - Lock & Lockhouse 28 - Part of Canal Quarters program

Hike in on towpath from Point of Rocks or Lander. 50.8 - Lock & Lockhouse 29 - Lander

This simple brick home with a deep front porch is the Lander Lockhouse #29. It can be found near Jefferson, Maryland. The lock here is constructed of granite from the Patapsco River and white flint stone from across the river in Virginia.

The last lock keeper to live in the home was Lewis Cross. The Cross family continued to rent the house for $20 a year even after the canal stopped operations in 1924. When Mr. Cross died in 1962, the lockhouse became the property of the National Park. In Civil War history, this was where John Mosby’s Confederate raiders crossed the river on the 4th of July in 1864 headed to the Calico Raid at Point of Rocks. When the raiders encountered a holiday excursion boat of treasury clerks approaching Lock 29 on the canal, they scared off the lockkeeper leaving the canal boat stranded. The treasury clerks forced to abandon ship made a run for it. At which point, Mosby’s raiders set their vessel “The Flying Cloud” on fire and then continued on their way. Today, the little town of Lander has a population of around 50, but when the canal was still operational, the town was busy enough to support a post office and two general stores. The Lander house is occasionally open for public tours. 39.3065217,-77.5581753

51.5 - Catoctin Aqueduct

Hike in from Landers Lockhouse 29 54.0 - Brunswick C&O Canal Visitors Center - 40 West Potomac St, Brunswick, Maryland 55.0 - Lock 30 - Brunswick boat ramp parking lot 39.311322,-77.631053 58 - Lock & Lockhouse 31

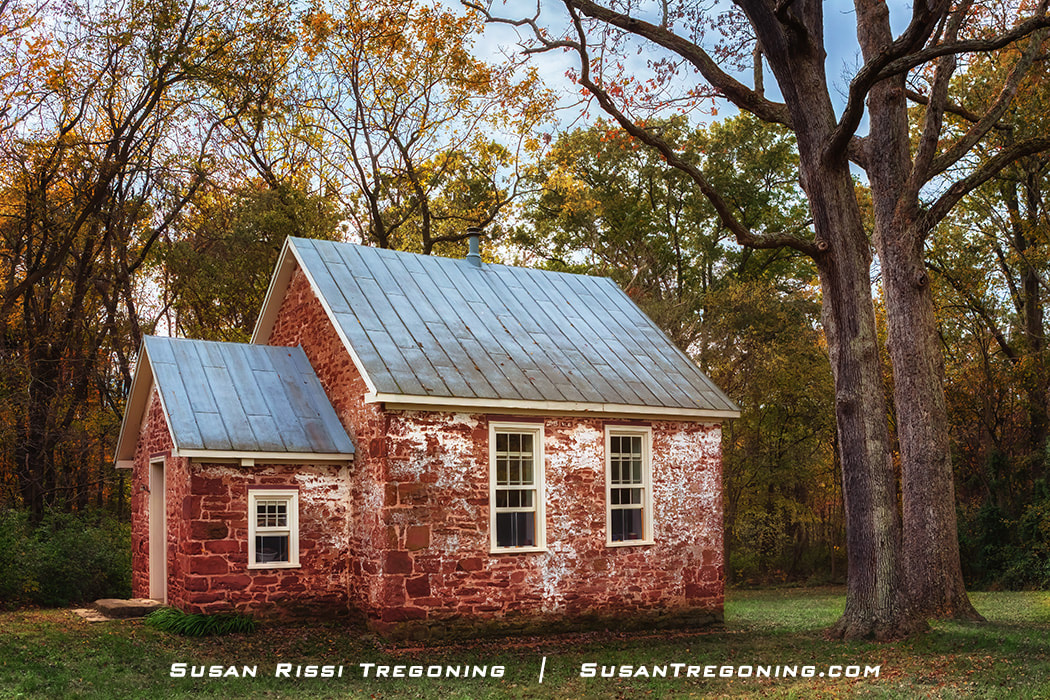

Lock & Lockhouse 31 are just over the Maryland state line from Harpers Ferry, West Virginia. This red-painted brick lockhouse is unique since most of the lockhouses along the C&O Canal were painted white so they were easier to see in the dark. Constructed around 1870, it cost $1720 to build.

There is parking along the road at the end of Keep Tryst Road. 39.3294461, -77.6810422

60.2 - Lock 32

60.7 - Lock & Lockhouse 33 Use the Appalachian Trail Bridge from Harpers Ferry to access the towpath. 60.8 - Harpers Ferry, West Virginia

|

|

The historic Bowles House located on the east side of Hancock was built in the 1790s. This farmhouse witnessed the arrival of the C&O Canal not far from its doorstep in the mid 1830s. The house’s residents sold goods and produce to the canawlers (canal boatmen) who passed through Lock 52 and the Tonoloway Aqueduct. Today this lovely old home is the Hancock C&O Canal Visitor Center.

|

Lock 52 and Tonoloway Aqueduct are just a short walk from the visitor center.

130.7 - Cohill Station Parking 39.645494, -78.2515301

134.0 - Lock 54 & foundation of the lockhouse

134.2 - Remains of Dam 6/ Guard Lock 6 is filled in/ Lock 55 - This was the terminus from 1842 - 1850 when the canal was completed to Cumberland.

1.8 miles from parking

Western Maryland Rail Trail Parking Lot - Pearre Rd.

39.6361864, -78.3228281

136.2 - Lock & Lockhouse 56 - .3 miles from parking

136.6 - Sideling Hill Creek Aqueduct

139.4 - Lock 57

141 - Fifteen Mile Creek Aqueduct

Construction started in 1838, but the C&O Canal Company ran out of money in 1842, and it sat unfinished until 1850. It was a site of labor riots and unrest that led to bloodshed and many laborers being blacklisted. There are many canal builders buried in the nearby St. Patrick's Cemetery.

The aqueduct was constructed out of hard flint stone quarried on the West Virginia side the Potomac River at Sideling Hill.

The aqueduct can be seen from the boat ramp at the Fifteen Mile Creek Campground in the little town of Little Orleans, Maryland.

39.6255985, -78.3854862

146.5 - Lock 59

149.6 - Lock 60

153.1 - Lock 61

154.1 - Lock 62

154.5 - Lock 63 1/3

154.6 - Lock 64 2/3

154.7 - Lock 66 1/3 - Notice that Lock 65 is missing.

Lock 65 - The Missing Lock - To save money, 10-foot lifts were used instead of 8-foot lifts. Lock 65 was not needed. Since contracts were already in place for locks upstream, they could not change the numbering.

155.2 Paw Paw Tunnel

When C&O eventually completed the canal, it was only wide enough for one boat at a time. Bottlenecks would occur, causing fights between the boatmen refusing to yield the right-of-way. Even though the rule was: the downstream headed boat would back up and leave the tunnel to allow the upstream boat to proceed, they would sometimes refuse. One time, a standoff went on for days until the boatmen built a fire upstream to smoke them out.

If you plan to walk through the tunnel, a flashlight is a must.

39.544616, -78.460582

162.4 - Town Creek Aqueduct - parking on site 39.5237668, -78.5433002

164.8 - Lock 68 & South Branch of the Potomac River

166.5 - Lock 69

166.7 - Oldtown

There are three locks within a half mile stretch of the canal here, Locks 69-71. They are the last of the composite locks along the Canal. By the time the Canal construction reached Oldtown, the C&O Canal Company was in financial trouble and struggled to get good quality stone to the Canal's far upstream locks. They allowed contractors to use whatever stone they could find and augment the construction with wood.

Lock 70 is in good condition. In 1906, a fire destroyed the Green Spring Road covered bridge over the canal, and damaged the lock which needed to be rebuilt.

This lockhouse is between two other very historical sites. The Michael Cresap House, located where Green Spring Road Ts at Opressa Street. Michael Cresap was the first white man born in Allegany County. He built the house in 1764, making it the oldest existing home in the county. Just a short distance past the lockhouse is one of the last privately owned interstate toll bridges in the country; it connects Oldtown to Greenspring, West Virginia.

There is a large parking lot at Lock 70.

39.540269, -78.6125302

Lock 71, one of last remaining composite locks, its lock pockets were later replaced with concrete.

173.5 - Patterson Creek Bridge ruins

174.2 - Steam Pumping Station

174.4 - Lock & Lockhouse 72 & Blue Spring - largest springs east of the Mississippi.

175.4 - Lock 73

175.5 - Lock 74 - has a 10-foot lift instead of the average 8-foot lift

175.7 Lock & Lockhouse 75

Although numbered as Lock 75, there are only 74 locks along the C&O Canal. In an effort to save money toward the end of the project, C&O had several 10-foot lift locks constructed instead of building the standard 8-foot lifts allowing them to skip lock number 65 in a four lock sequence. The locks were not renumbered since contracts were in place and construction already underway for upstream locks.

Lockhouse 75 is one of the final lockhouse to be built along the canal and one of very few remaining log cabin lockhouses. It was damaged in the March 1936 flood after the canal had already closed, and then a dust beetle infestation nearly finished off the structure. While the log home sits on its original foundations, only a few original timbers could be used in this 1978 reconstruction.

39.587555, -78.741766

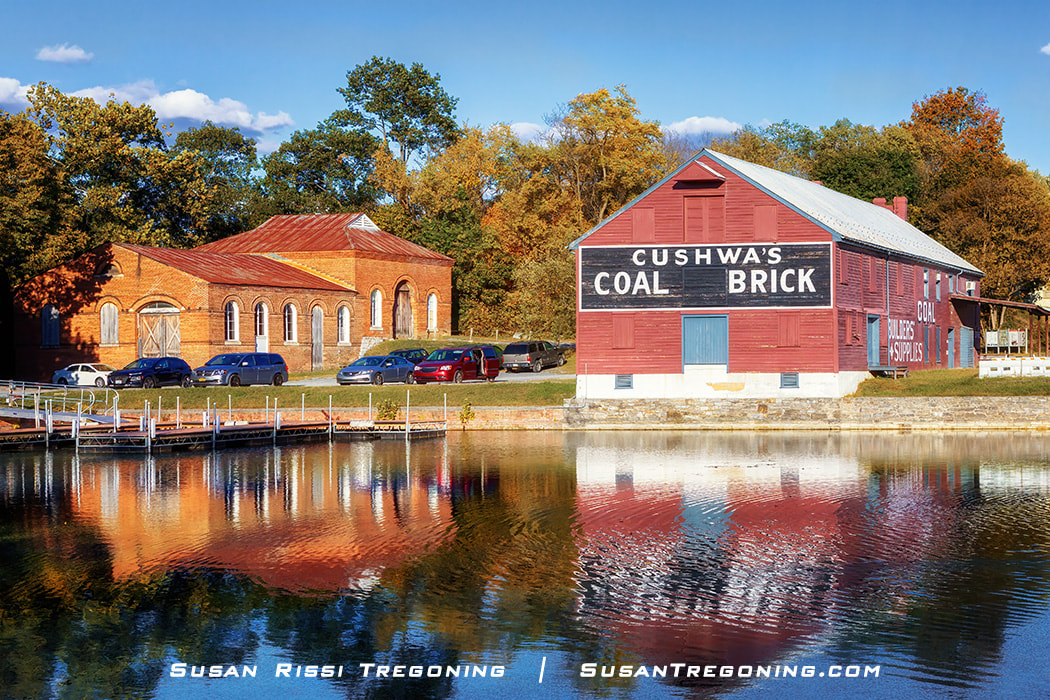

184.5 C&O Canal Terminus

When the COCCM began planning this project, no boats or blueprints were in existence. Canal boats had to be researched and plans recreated before the building could start; the replica ended up costing over $100,000 to complete.

After its dedication on July 11, 1976, the COCCM operated it for 23 years conducting interpretive boat tours during the warmer months.

The Cumberland canal boat sits on the towpath behind the

Fairfield Inn & Suites at 21 North Wineow Street

184.6 Cumberland

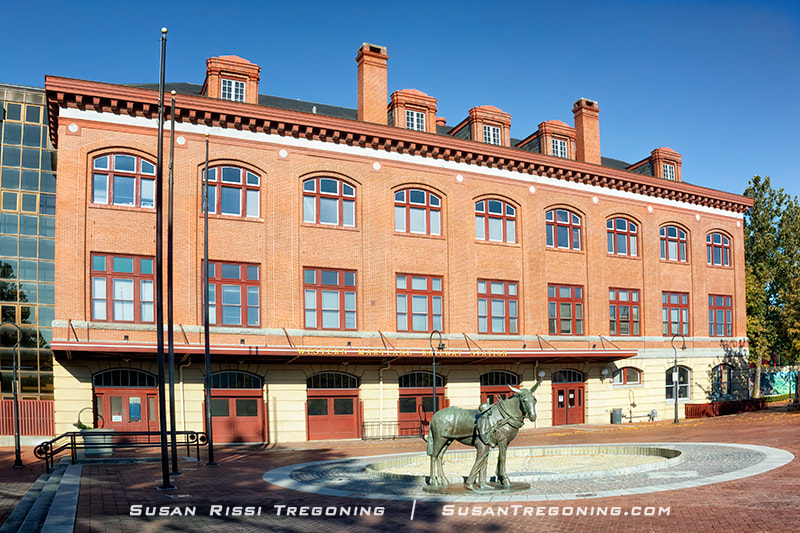

Western Maryland Railway Station - 13 Canal Street, Cumberland, Maryland

Though the 1990s, the station underwent a series of renovations. Today, the building is the center of the Canal Place Preservation District. The depot houses offices for the Western Maryland Scenic Railroad, a sightseeing excursion train through the Blue Ridge Mountain Foothills.

All the visitor centers were closed when I visited. A downloadable park map is available, I never found a map anywhere until reaching my final stop at Great Falls Tavern. Luckily, I planned for that.

I have created a detailed Google map with all the canal locations.

|

About the Photographer

Susan Rissi Tregoning is the 8th photographer in the past four generations of professional photographers in her family. After a long career as an art buyer and interior designer, she put her career on hold in 2006 to travel with her husband and his job. In the process, she found her “roots” again, developing a photography obsession far |

This is a lovely webpage. However, the violence along the upper part of the canal in 1838 and 1839 was neither race riots nor even riots. It was labor unrest and a rising labor militancy by immigrant Irish laborers who were beginning to organize and attempt to force improvements in pay and working conditions with the use of threats and violence. The laborers of other ethnicities who were attacked in an effort to drive them from the canal, were taking jobs from Irish workers and they offered the contractors a way to avoid the growing Irish militancy. There was actually 3 kinds of laborer violence on the C&O: (1) Irish on Irish (e.g. Jan. 1834 between Irish workers at Dams 4 and 5); (2) this kind of labor organization and militancy laregly confined to limited incidents in the late 1830s; and (3) "celebratory/recreational violence" associated with drunken behavior when the men were not working. The virtual destruction of a shanty tavern in Oldtown involving large numbers of celebrating Irish, is an example of the latter. As a C&O Canal historian, I have never found an example of a racial riot or incident of group violence along the canal during the construction era, that was about race or ethnicity although the Irish did also oppose the local farm boys who would be hired when available but leave the canal when there was work on the farms. They took jobs the Irish needed full time, and made it possible for the contractors to fill them on a part time basis.

Leave a Reply.

Author

I am the 8th photographer in 4 generations of my family. Back in 2006, my husband accepted a job traveling, and I jumped at the chance to go with him.

I blog about long scenic drives and places that I find interesting around the United States.

Categories

All

Alabama

A Travelers Musings

Hawaii

Illinois

Indiana

Iowa

Louisiana

Maryland

Michigan

Minnesota

Mississippi

Missouri

Nebraska

New Mexico

North Carolina

Pennsylvania

South Dakota

Tennessee

Texas

Virginia

Washington DC

West Virginia

Wildlife

Wisconsin

Wyoming

Archives

June 2024

April 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

October 2023

June 2023

April 2023

February 2023

September 2022

June 2022

April 2022

January 2022

November 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

February 2021

December 2020

February 2020

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

February 2019

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

March 2017

January 2017

This website uses marketing and tracking technologies. Opting out of this will opt you out of all cookies, except for those needed to run the website. Note that some products may not work as well without tracking cookies.

Opt Out of Cookies

RSS Feed

RSS Feed